Disco Elysium es el Planescape de esta generación: Tormento

En una lista de los diez mejores juegos de rol jamás creados, será difícil encontrar a alguien que, después de jugarlo, no haya incluido Planescape: Torment en alguna parte de su selección. Para este autor, es el pináculo del género: un estupendo guiso de atmósfera, exploración y una escritura tremenda y evocadora que nada estuvo cerca de tocar.

Es decir, hasta ahora.

La calidad de la escritura es inmediatamente evidente.

La calidad de la escritura es inmediatamente evidente.

Verás, ZA/UM Studio, con sede en Estonia y el Reino Unido, ha estado injertando un título que muy bien podría poner patas arriba todo el género de los juegos de rol. discoteca elíseoes un juego de detectives que te presenta como un alcohólico que apenas funciona en un caso, donde se requiere tu ingenio para luchar contra las facetas de tu propia mente tan a menudo como los personajes que encuentras. Si eso suena como una miga sabrosa para atraerte, te espera un delicioso pastel enorme desde el momento en que te sientas y comienzas a leer las magníficas resmas de diálogo y texto descriptivo esparcido sobre cada elemento del juego. No es una exageración decir que esta es la escritura más emocionante, atmosférica y accesible para adornar un juego de rol basado en texto desde la obra maestra de Black Isle y, nos atrevemos a decirlo, posiblemente podría ser aún mejor. Hablamos con algunos miembros del talentoso equipo del estudio para obtener más información sobre el desarrollo de este título enormemente ambicioso.

De la mesa al escritorio

La prosa de Disco Elysium tiene un tono muy orgánico que parece sacado de los juegos de rol de mesa, aunque resulta que esto no es una coincidencia. “Llevo jugando al lápiz y al papel desde que tenía quince o dieciséis años”, dice el diseñador principal Robert Kurvitz. “Soy algo así como un evangelista, y comencé a verter en ello mis ambiciones como novelista. Estaba jugando con mis amigos artistas jóvenes en ese entonces y nos volvimos muy intelectuales con él. Creo que es tan buena como la narración y la cultura. El problema es que no puedes grabarlo. No puedes llevarlo a ningún lado. Me estremezco al pensar en todos los cientos de juegos de lápiz y papel realmente buenos que simplemente se evaporan, así que decidimos construir nuestro propio mundo y terminamos dedicando gran parte de nuestras vidas a tratar de resumir esto en un video. juego.”

Kurvitz tiene razón. Para cualquiera que esté familiarizado con los juegos de rol de mesa, ya sea Dungeons & Dragons , Cyberpunk o cualquiera de los innumerables escenarios y escenarios disponibles, no hay nada tan mágico como lograr algo aparentemente imposible con un personaje de su propia creación simplemente formando una idea y ejecutándolo con una tirada de dados. Capturar ese momento de tensión en un videojuego aún no se ha logrado por completo. A medida que los juegos de BioWare se desarrollaron desde la sensación isométrica hogareña de Baldur’s Gate hasta el suave Mass Effect: Andromeda, más y más de esa personalidad de mesa se disipó. Fue esta necesidad de transportar la construcción orgánica del mundo fuera de la narración verbal lo que influyó en la propia novela de Kurvitz, y esto a su vez condujo al éxito y la importante financiación necesaria para crear Disco Elysium.

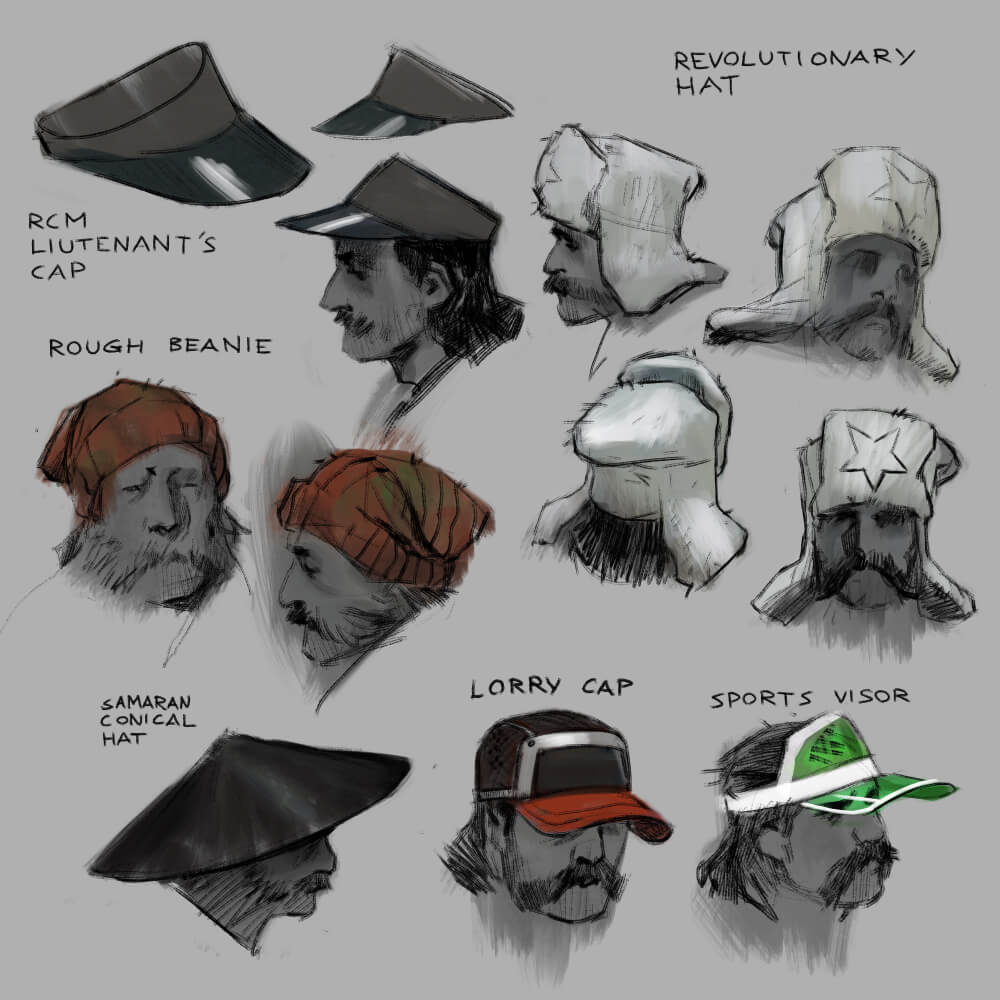

El arte conceptual muestra un meticuloso nivel de detalle incluso en los aspectos más pequeños del juego.

El arte conceptual muestra un meticuloso nivel de detalle incluso en los aspectos más pequeños del juego.

Sin embargo, el juego nunca tuvo la intención de crecer tan rápido como lo ha hecho. Ha sufrido numerosos cambios, entre ellos la sabia decisión de cambiar el título de Sin tregua con las furias a algo más extraño y memorable, pero una vez que los escritores comenzaron a poner sus ideas en papel, las cosas crecieron rápidamente.

“Resulta que el nivel de detalle o realismo que buscamos tiende a explotar las cosas”. reflexiona Kurvitz. “Pensamos que [ No Truce With The Furies ] iba a ser una primera prueba de manejo para compartir lo que hemos estado construyendo durante, bueno, la mayor parte de nuestra vida adulta. Pero a medida que avanzábamos en el desarrollo, el juego realmente comenzó a animar a la gente. Realmente siento que tenemos un gancho de historia único en la vida, que no es fácil de encontrar para un juego de rol. Así que sí, tuvimos que cambiarle el nombre a algo más comercial y darle un golpe a Estados Unidos con él”.

Arte imitando la vida

Para entender la ambientación de Disco Elysium, es necesario comprender los antecedentes de sus creadores. ZA/UM Studio comenzó como un movimiento cultural, y uno fantásticamente fracasado por su propia admisión. “Éramos en su mayoría personas de izquierda, no muy populares hoy en día en Europa del Este”. recuerda Kurvitz. “Nos metimos en escándalos políticos. Pero logramos componer un grupo de personas que tenían locas ambiciones por la cultura, por la pintura, por la música, por la poesía. Ese grupo normalmente no funcionaría bien en una compañía de software, pero supimos de inmediato que si queríamos armar esto, no podía ser cyberpunk o alta fantasía o fantasía oscura. Nunca iba a inspirar a estas personas lo suficiente para trabajar o dar cuatro o cinco años de sus vidas si no tuvieran relaciones humanas reales, o reflexionar sobre el mundo en el que estamos. Creó una necesidad muy real de tener una configuración o una IP que se adaptó a eso,

Since the usual fantasy staples were off the table, the setting and story were soon swapped out for something more realistic with underlying geo-political themes. Doing so gave the writers freedom to express themselves without being constrained by typical RPG naming tropes. The game name may make it obvious, but as writer Helen Hindpere elaborates: “Though it takes place in an alternative world, we just really liked using elements from the 70s. For instance, there is no internet yet and the first computers are only just being developed. We really liked the buzz of the 70s, and incorporated many elements of that into the world.”

The artwork has a industrial Soviet flavour which touches on the team’s eastern European heritage.

The artwork has a industrial Soviet flavour which touches on the team’s eastern European heritage.

Indeed, the initial locations are deliberately mundane: an apartment; a cafe; a rundown city block. But they help ground the game to allow the more innovative mechanics such as skills to establish themselves. Realism also has its conveniences. “One of the things I got really excited about was telephones,” adds Kurvitz. “You need to have telephones in a story, or you get into Game of Thrones problems with people sending ravens for four months and destroying spatial logic.”

Why choose a detective story? Hindpere has the answer. “Solving a mystery is the easiest way to make things interesting for the player,” she notes. “It propels you to ask questions about the world around you, plus it allows us to explore authority. Revachol [the game’s setting] is a very political city, and people don’t really like cops there — so you’re already an antagonistic character.”

“Solving a mystery is the easiest way to make things interesting for the player,” – Helen Hindpere, writer.

That’s something of an understatement. As the game begins, you wake up on the floor of a filthy apartment in just your underwear, sporting a stonking hangover. The first thing you have to try and do is work out who you are and why you’re there — echoes of Planescape: Torment permeate throughout, but the feelings you have towards your protagonist are starker. He both revolts and delights with his actions and words, whether plucking up the courage to look in the mirror and see the abomination of his sleep-deprived face, or simply combing through the apartment to find his clothes in an attempt to make himself presentable.

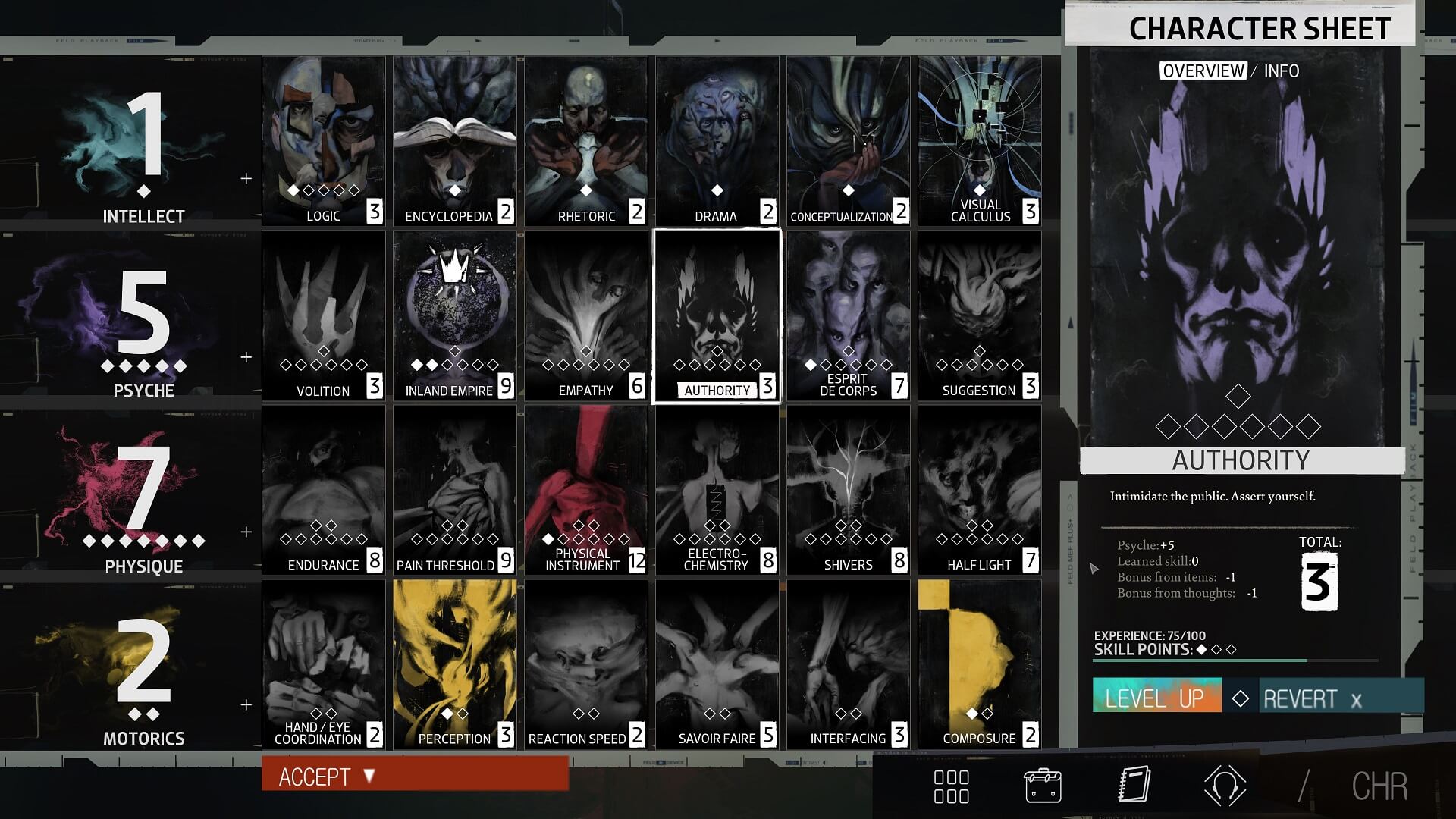

Mad Skills

Your apartment is where you’re introduced to one of the game’s notably different elements: its skills. Where most RPGs focus on variations of recognisable, practical competencies such as strength or intelligence, Disco Elysium digs deeper. Within each of its four core sets of skills (Motorics, Physique, Intellect and Psyche) are six selectable traits, which not only offer up branching dialogue, quests and lore, but literally interact with each other. The skills are talking facets of your mind, with conversation trees of their own. When you’re speaking to a suspect, your skills will often intervene or open up dialogue options for you to pursue a line of questioning, but they may also hinder each other.

The portrait for the Drama skill feels appropriately OTT.

The portrait for the Drama skill feels appropriately OTT.

As an example, Logic is an Intellect skill which determines how “right” you are about something, or at least, how right you believe you are. It is far too easily manipulated by flattery, so if you’ve picked another Intellect skill such as Drama — which can sniff out a lie from a hundred paces — it’s possible that these two skills will start having a full-on argument in your head during an interrogation, particularly if the suspect is silver-tongued. Meanwhile, the Psyche skill of Volition represents your inner good guy, which is almost certainly going to butt heads with the Physique skill of Electrochemistry: your need and capability for taking drugs. A high Electrochemistry skill lets you consume narcotics to overcome difficult checks in your investigation, but will undoubtedly lead you down the road to addiction. Indeed, quests specifically based on your need to get your next hit can only be accessed by having Electrochemistry in your toolset, but doing so will obviously be at the expense of your morality.

When you start to realise just how much effort has gone into creating each of these twenty-four different skills, not only in how they are directly used but also their interactions with each other and you, and then tally in the individual paths and side quests each skill can take you down, it’s genuinely staggering. Kurvitz would like nothing more than for other game developers to adopt this approach to skills in RPGs. “I really hope people steal this idea from us — to turn skills into people you can talk to,” he says. “It’s a step you need to make this kind of story-based game personal to the player. It gives you a feeling that you are involved in that wall of text, that you gave that skill a voice. The story wouldn’t be possible without them.”

The skill range is so vast and deep that seeing everything the game has to offer is practically impossible.

The skill range is so vast and deep that seeing everything the game has to offer is practically impossible.

Putting points into a skill may not, however, give you the outcome you expect. Your skills have egos of their own and want you to listen to them. If you don’t, or worse, if you try to utilise them and fail, they may react hard. For instance, if you have Suggestion from the Psyche set and try to influence someone, but fail and end up losing face, Suggestion may go off the rails and force you to do something you might not want to do. It’s Disco Elysium’s way of simulating thinking, a concept intangible enough in real life, let alone having it represented in a game. Kurvitz continues: “The struggle of composing sentences, hearing background fears, my conceptualisation giving me a bad joke I’m not going to act on, and so on…there’s a kind of anxiety and tension of being alive and thinking.”

Heavy stuff indeed, which makes it all the more impressive that ZA/UM has progressed this side of storytelling — the internal mechanisms which dictate what we do and say as a character — in a way that has simply not been done before. Many RPGs such as Baldur’s Gate and Dragon Age incorporated puzzle elements into their side quests, while more action-oriented games like the Deus Ex series went in heavy on minigames. With Disco Elysium, this isn’t necessary, as Hindpere explains, “One of the biggest puzzles you’ll encounter is yourself, and specifically whether you should trust your skills,” she says. “Quite often your skills will tell you to do something, but it then turns out that doing that thing wasn’t actually such a good idea.”

Argo Tuulik, lead writer on the game, agrees that the way skills are portrayed tries to closely imitate a person’s constant internal struggle in life. “You might have an irresistible urge to go for a cigarette. This is just a thought inside your head, but it’s not always a good idea — it’s the same for our skills. They may give you bad advice.”

An interesting side effect of creating something so recognisable about human failings within a game system is that players can instantly connect with it. “We didn’t need to tutorialise any of it,” Kurvitz grins when asked how quickly players picked up using each of the skills in conversation. “People just said ‘Yeah, I have that.’ Most people say that [the representation of skills] is sort of the situation they’re in generally — everyone is in their own head.”

There are over 80 different items of clothing to wear – all with unique properties or effects.

There are over 80 different items of clothing to wear – all with unique properties or effects.

Another trick ZA/UM uses is giving each of the skills portraits, like human faces which are distorted or altered to represent a particular skill. Talking to something with a mouth and eyes helps solidify the skills even further as unique characters. Each skill has its own personality, building up a picture of your anti-hero as he drags himself from location to location. You can almost smell the stale stench of alcohol on his breath through the monitor while he fumbles to find out where one of his shoes has disappeared to (one of the first quests you’re given). Yet this is a mere hors d’oeuvre, the tiniest slice of repugnance you’ll feel in comparison to the gut-wrenching scene when your detective has to deal with a corpse hanging from a tree.

“The cadaver was nasty stuff,” Kurvitz laughs. “I researched it and wrote it for about five months, and we thought ‘we’re never going to get this released, ever.’ It takes about thirty minutes if you’re precise with it and I wanted there to be the most gruesomely detailed autopsy scene ever put into a game, where your skills interrupt and tell you things about it.”

On top of this is the “Thought Cabinet”, an inventory for Thoughts — skill modifying statuses which you may stumble upon depending on the choices you make. An example thought is “Hobocop”, where if you let your character’s mental state deteriorate to a point where he can’t remember where he lives, he will go and make a home in a dumpster. It doesn’t end there though: you can actually start taking garbage to the shop in exchange for cash. Like armour in D&D, Thoughts give you bonuses as well as penalties to your skill checks, offering you further specialisms in your role-playing. Here, they aren’t just a stat adjustment, but a completely new facet of gameplay for you to explore, and again, depending on the skills you’ve picked, you may end up being led down a different path than the one you envisaged when you set off.

There are over fifty Thoughts to collect, but you won’t be able to get them all in a single game and their purpose won’t be clear to begin with. You’ll be given the Thought’s name and a snippet of information about it, but that’s it. Only as in-game time passes will you decipher what each Thought does and the effects that they may have on you. Not all Thoughts are positive. In fact, there’s one Thought that will make you fail every skill check you make — temporarily at least — but that in turn may uncover new Thoughts. Some of them open up new pathways in the game, sending you off to talk to other people. Working out what Thoughts mean is a process called “internalization” which may take minutes or even days of in-game time, but the end result is a Thought that you can either store in your Cabinet along with its associated benefits (and penalties) or discard by expending a skill point. As the Thought Cabinet has limited slots, choosing which Thoughts you want to keep or discard is a tricky process. It’s yet another intriguing element of your character build.

Painterly Ambitions

When playing the game, one of the most striking elements outside of the writing is the visual design — a hybrid of painted environments, oil-painted character portraits and animations far more detailed than one might expect from an isometric RPG. This comes courtesy of art director Aleksander Rostov, a classically trained oil painter, and a concept artist enigmatically known as Kasparov who has a similar background. The artists take even the most minor aspects of their craft seriously: the character portraits were worked on for over seven months to make it look like they have brushstrokes through them, after the original shadow maps made everything look “too round”. They discounted using 3D CGI immediately when it came to designing the world. “They don’t like the look of it, they don’t like the feel of it, they don’t like the glistening of the skin or the subsurface scattering,” Kurvitz laughs. “The last time they liked it was in the late 90s, in Starcraft. It was their ambition to come up with a new aesthetic. Just like our writers have the ambition to create a new IP in a modernist setting, it’s their ambition to do something that other people want to emulate because they want to see this kind of brushwork aesthetic in the world.”

There are plenty of stats available for you to pore over, should you wish.

There are plenty of stats available for you to pore over, should you wish.

ZA/UM is an indie studio — although you wouldn’t have guessed it from the sheer breadth of content poured into the game — so at some point a line had to be drawn under costs. For Disco Elysium, it was voice acting. Similar to Pillars of Eternity and Torment: Tides of Numenera, while many of the conversations do have an initial voiced segment, the remainder is pure text. Hindpere notes that while hiring voice actors is certainly expensive, there is another reason to focus on text. “Voices really gives you an idea of a person[‘s character], but quite often voice acting and your speed of reading are different. So that’s why we decided to have dialogue voiced at the beginning, so you can then read on at your own tempo.”

Given the volume of text, it’s probably for the best. At one point you can have a conversation with an NPC about cannons. You, like the protagonist, may know nothing about cannons, but that doesn’t stop you being able to egg on the NPC to go into more and more ludicrous detail about artillery. And the best thing about this? It’s genuinely interesting. It may have nothing to do with the story, but the confluence of setting, character and personality all work to make the lengthy dialogue session both believable and hilarious. And you’ll end up learning a lot about a subject that you might not have even considered before.

How did that sequence even end up in the game? Hindpere laughs when we ask her. “So many things have started out as jokes, and we’ve thought ‘We can’t put that in, this is a serious game!’. But then we think about it a bit and realise that we can. For instance, you can sing karaoke in the game which is something that started out as a fantasy throwaway idea. The cannon chat is another example. One of the team is really into cannons, so we added it — and it survived the edit because one of the programmers said that they really enjoyed reading that part, so we left it. We write what we want to read. It’s our game.”

Some Kind Of Superstar from the Thought Cabinet. What does it do? We’ll find out soon…

Some Kind Of Superstar from the Thought Cabinet. What does it do? We’ll find out soon…

While not a traditional party-based RPG, you aren’t alone in your mission (should you work out what that mission is). You have a non-controllable partner, Lieutenant Kim, a by-the-book cop who also acts as an expository outlet for your situation and the world around you. While Disco Elysium wouldn’t work with multiple characters to manage, you won’t lose out on the party dynamic which makes so many RPGs wonderfully complex creatures. Here, it’s your skills which effectively act as your companions. Where BioWare asked you whether you wanted to follow Jaheira’s requests in Baldur’s Gate, in Disco Elysium you need to choose which parts of your own mental make-up you’re going to go along with.

Ultimately, you have to decide whether to listen to your thoughts or disregard them — and the repercussions of doing either may land you in hot water. While there are battles, they aren’t the typically clunky scenarios which felt so out of place in Planescape: Torment. “We like to think of it as dialogue-based combat,” Hindpere says. “Combat definitely happens, but you can’t just go and shoot someone in the face. Placing combat in dialogue gives it a psychological depth, making you really think ‘OK, what am I going to do next?’. And again, it’s skill-based — skills really matter in combat.”

A Political Animal

The way the game tries to wrest agency from the player is a refreshing take on the usual fantasy genre trope of a fated hero coming to power. Does Kurvitz think that the studio’s Estonian roots had a part to play in making the protagonist someone who isn’t fully in control? “For me, definitely,” he nods. “The global culture is an empire culture. This is a culture made by winners on boats who sailed to new worlds and then committed genocide. I come from a lineage of serfs — which is a nicer word for slaves — who were freed ten years before the American slaves. My experience of western capitalism comes after the fall of the Soviet Union, which was a really, really bad time for people in eastern Europe in the 90s, whichever way you slice it. So, I never felt like a piece that fit into the western scene, I felt like I was more of a Soviet person for some reason. So naturally, I wasn’t going to make a game where I stepped into ceramic armour with a FAL automatic rifle and win. I was going to make one where you’re heartbroken and fighting against yourself and the world.” This is a feeling which resonates with everyone in the studio, and Tuulik agrees. “The story of the underdog has always been more interesting than the ‘Chosen One’.”

Becoming a hobo, while an optional diversion, will still have an impact on your game.

Becoming a hobo, while an optional diversion, will still have an impact on your game.

Politics in games are often divisive. If there’s a whiff of any kind of political messaging in a story, you are guaranteed to incense some players — even those who haven’t played the game. Steam is littered with review-bombed games where the focus of the objection isn’t on the gameplay, but that the developer dared to address political themes. The first episode of Life Is Strange 2 invoked the ire of some players for daring to comment on the rise of right-wing politics. We thought while the messaging was a little clumsy, it didn’t detract from a brilliant game; we certainly weren’t disappointed that it was included. Disco Elysium looks set to push this further and provide social and political commentary on numerous world issues through the lens of its downtrodden detective.

“The story of the underdog has always been more interesting than the ‘Chosen One’” – Argo Tuulik, lead writer.

“I can’t write without writing political jokes,” Kurvitz comments. “Politics is so alive with tension and language. As a writer, I’m drawn to interesting worlds and people interacting with each other, and there was no other way than to make it political. The game is set in a modern world. If you have telephones in the world, someone has manufactured them, someone has the patent, someone put it together, someone has to pay for it, someone isn’t going to get a telephone for forty years, and so on. A world without politics is a hollow world. But my suggestion to video game developers would be to not do it. You get into shit with politics; there’s almost no upside. I would have liked not to talk about these things head-on because they take so much playtesting and writing not to fuck it up. If you go into it and you don’t know what you’re doing, you’re not going to come out well.”

The denizens of Revachol are a unique bunch; some creepy, some hilarious.

The denizens of Revachol are a unique bunch; some creepy, some hilarious.

The game also refuses to pull punches in the lengths to which players can roleplay. You can make your detective become a racist, a lecher, or side with a homophobic NPC, and then you can follow through with those choices in the game. Yet the reason some players are likely to feel uncomfortable is because of the realism in the writing rather than the overarc